修道知音

Cultivating the Dao

Knowing the Tone

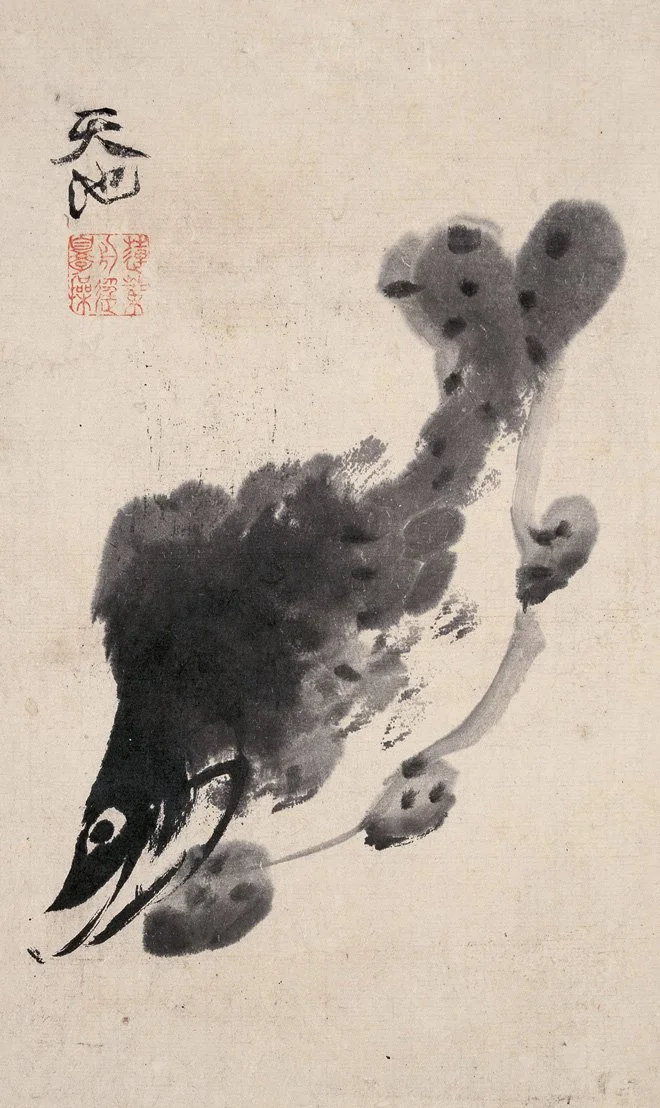

Image by Zhou Dongqing 周東卿

Xiūdào 修道

Cultivating the Dao

Tradition-Based Daoist Education 道學

Daoist Study-Practice 學行, rooted primarily in Classical Daoism, with additional influence from formal religious ordination training in the Quánzhēn Huàshān lineage 全眞華山派, and the Qīngjìng Dào 清靜道 movement.

Our approach is primarily meditative, quietistic, and hermeneutical, with additional cosmological and eremitic dimensions.

Daoist practice is informed by study and interpretation of Daoist texts, notably the Zhuāngzǐ 莊子 (Nánhuá jīng 南華經), Lǎozǐ 老子 (Dàodé jīng 道德經), and Nèiyè 內業. Daoist textual study is, in turn, informed by experiential practice, primarily solitary seated apophatic meditation.

We meet weekly on Sundays over Zoom.

All are welcome; no prior experience required.

zhīyīn 知音

Knowing the Tone

The term zhīyīn 知音 carries a dual meaning. Originally, it refers to a story first found in the Lièzǐ 列子, about the famous Qin (zither) player Bóyá 伯牙 and the woodcutter Zhōng Zǐqī 鐘子期.

Though they shared nothing else in common, whenever Bóyá played his instrument, thinking of the grandeur of high mountains or flowing water, Zhōng would immediately recognize the inspiration. Whatever Bóyá played, Zhōng understood his music and knew the tone.

After Zhōng died, Bóyá broke the strings of his Qin and vowed to never play again, for no one else could appreciate his music to the same depth.

Zhīyīn, “knowing the tone,” is an idiom that refers to a true friendship based on deep understanding and shared affinity. We hope to foster a community of 知音者 - those who ‘know the tone’ - and support each other as dàoyǒu 道友 (companions of the Way).

莫逆於心遂相與為友。

There was no contrariety in their heart-minds; consequently, they gathered together and became friends.

Zhuāngzǐ 5

-

The second reference to zhīyīn 知音 occurs in the context of Chinese poetry of the medieval period. Here, the term describes someone who appreciates the finer qualities of a poem, which may include: mastery of the technical tonal and parallelism rules of regulated verse, musicality, and/or deep and subtle insights that the poet evokes but does not communicate directly.

Though court and literati poetry styles dominated how poems were crafted and received in East Asian culture, there was also a tradition of ordained practitioners and religious lay(wo)men who used this medium to transmit doctrinal teachings, or communicate the authenticity and profundity of their own cultivation.

This raises a seemingly paradoxical issue: if attaining the Dao 得道 involves an ontological transformation rooted in an undefinable and unspeakable teaching (玄之又玄 Mysterious, and again more mysterious) that cannot be discussed (道可道非常道 The Dao that can be spoken is not the constant Dao), then how can poetry be used to communicate the teaching that cannot be talked about 不言之教 ?

Without denying the above, poetic and paradoxical language can also be used as a tool to bypass habituated patterns of thinking and dismantle the hegemony of over-rationalization, leading to glimpses of the ineffable, mysterious current 玄風 of the Dao. Furthermore, Daoist aspirants may take inspiration from the metaphors and imagery of poetry.

The composition of poetry can serve as an expression of wúwéi 無為, the effortless non-action of the adept dedicated to apophatic cultivation. An aligned and still heart-mind attuned to the Dao is like a clear mirror that can reflect the suchness ⾃然 of the myriad things, expressed in verse.

In the future, we hope to offer opportunities to read poetry together, whether in translation or its original form (literary Chinese), and build a foundation through study of its historical developments and various literary conventions. We further endeavour to foster a community of Daoist practitioners that writes and shares poetry together.

今我則已有謂矣,而未知吾所謂之其果有謂乎,其果無謂乎

Now I have just said something! But I don’t know if what I said has truly said something or whether it hasn’t said something.

Zhuāngzǐ 2

Note:

There are currently no active poetry meetings over the winter.

All classes given in English.

Xu Wei 徐渭